My breakfast has been the same most every day for several decades: shredded wheat with soy milk.

Shredded wheat, along with corn flakes and grape-nuts, is one of the staple American cold breakfast foods invented at the end of the 19th century by vegetarian food faddists. They have made contributions, sometimes major ones, to the development of consumer marketing, intellectual property law, and vocabulary.

In addition to specific sources cited below, the following books cover the threads that intersect here in more depth:

- Cerealizing America: The Unsweetened Story of American Breakfast Cereal presents that history from the point of view of popular culture and consumerism.

- Vegetarian America : A History is full of additional interesting characters with nothing to do with breakfast, like Emarel Sharpe Freshel, who lived not too far from here (where her home stood, there is now a BC dorm), where she regularly had high-society vegetarian get-togethers. She also organized an annual vegetarian Thanksgiving at the then new Copley Plaza. She knew Tolstoy and Shaw (who may have given her the nickname Emarel from her initials M. R. L.), and met Dharmapala when she attended the 1893 World's Parliament of Religions as a Christian Scientist. (The dedication of the somewhat biased The Incredible World's Parliament of Religions has her converting to Buddhism as a result of this, and it may well have been an eventual influence, but other sources indicate that she did not leave that church until 1917 over its stance on entry into WWI.) She designed her next-door neighbor's house and may have done the original sketches for the design of the highly prized Tiffany Wisteria lamp, as part of her instructions to Tiffany for decorating her home. This has been called into question by the discovery earlier this year of the letters of Clara Driscoll, where Driscoll takes credit for it. I am hardly an expert, but these two claims do not seem to actually be in conflict, if we assume that the sketches only gave a rough description of wisteria in leaded glass. Emarel's grand-niece has a blog, where bits of family history seem to show up occasionally.

- Listening to America : An Illustrated History of Words and Phrases from our Lively and Splendid Past has a few pages (131-133) on breakfast food names, among similarly sized essays on many other topics.

It all starts with Sylvester Graham, inventor of Graham flour, whole wheat flour made by adding back the bran and germ, but more coarsely ground than the base white flour, and the Graham cracker. Graham advocated abstinence from pretty much everything, including meat, alcohol, tobacco, caffeine (okay so far), sex and chocolate.

James Caleb Jackson was a Grahamite who promoted hydrotherapy and a vegetarian diet as cure-alls. In 1863, he developed the first industrial dry cereal, made from granules of Graham flour, which he called Granula. He ran an institution in Dansville, NY, called Our Home on the Hillside and so formed a company to sell his cereal known as the Our Home Granula Company. They also made a grain-based coffee substitute known as Somo.

Jackson's water cure and cereal found favor among Seventh-day Adventists, who have a strong vegetarian tradition. (There used to be a vegetarian restaurant in downtown Boston run by Adventists. It was a victim of the Big Dig, barely surviving during the endless construction and then unable to afford the jacked up rents once that was over.)

John Harvey Kellogg was an Adventist doctor who ran their Sanitarium in Battle Creek, MI. Here he carried out experiments to develop an improved cereal, which he also called Granula. When Jackson objected, he changed the name in 1881 to Granola. Some sources say that there was only the threat of legal action, others that Jackson actually won a judgment against Kellogg (though none give a case reference). We will see even more of this kind of discrepancy presently. Here are a couple ads for the Battle Creek Sanitarium's Granola.

Modern granola appears in the mid-1960s. The earliest reference to modern granola in the OED is from this 1970 Time magazine article, though uses from a year or more before that aren't hard to find in ads in digitized newspaper archives. Any connection with the earlier kind is not entirely evident, but nor is it ruled out. Though there are several other claimants, a major promoter of granola was Layton Gentry, profiled in Time as Johnny Granola-Seed. In 1964, Gentry sold the rights to a granola recipe using oats, which he claimed to have invented himself, to Sovex Natural Foods, a company making a concentrated paste of brewers yeast and soy sauce by that name, founded in 1953 in Holly, MI by the Hurlinger family, and bought in 1964 by John Goodbrad and moved to Collegedale, TN. In 1967, Gentry sold the West Coast rights to Wayne Schlotthauer of Lassen Foods in Chico, CA. The Hurlingers, Goodbrads, and Schlotthauers were all Adventists and it is possible that Gentry had some Adventist association. Furthermore, in Joe Klein's article “A Social History of Granola” in the Feb. 23, 1978 issue of Rolling Stone, Schlotthauer claimed that his grandmother was making something called “granola” when she came over from Germany in 1912 and that he was making small batches of the wheat-based version in 1957 at his father-in-law's health food bakery (which would become Lassen Foods). In 1972, Pet Milk (later Pet Incorporated) introduced granola under the Heartland Natural Cereal brand; it was the brainchild of Jim Matson, who is the main subject of Klein's article. At almost the same time, Quaker introduced Quaker 100% Natural Cereal, followed shortly by Kellogg's Country Morning and General Mills Nature Valley. In 1974, McKee Baking, makers of Little Debbie snack cakes, purchased Sovex. In 1998, they also acquired the Heartland brand and moved its manufacturing to Collegedale. (That Heartland page claims that Matson introduced Heartland Natural Cereal in 1968, but that appears to be before he was even working for Pet.) In 2004, Sovex's name was changed to Blue Planet Foods. This JSTOR article (and a couple that it references that are also in JSTOR and to which it'll nicely hyperlink) relates granola to other -ola neologisms, including generalizations of payola for all kinds of financial scandals and foods like Mazola. Though it does not mention it, canola also fits the pattern. As near as I can determine, that name came from a 1978 committee for establishing a trademark to regulate its quality. Imagine if it they had gone with CanAbra oil or kept LEAR (for low erucic acid rapeseed) oil.

Meanwhile, back in 1892, a Denver lawyer and entrepreneur named Henry Perky had teamed up with a Watertown, NY machinist named William H. Ford to invent a machine (U.S. Patent 502,378) to make shredded wheat. Perky set up his Cereal Machine Company in Denver, where he soon realized that selling the product would be superior to selling the machines for home use. So he moved to Boston (on Ruggles St. in Roxbury, I think, though I'm not sure where) and then Worcester and then to Niagara Falls to take advantage of the cheap hydroelectric power.

The standard version of the story is that Perky suffered from dyspepsia and sought an easier to digest substitute for bread. At a hotel in Nebraska he saw a man eating boiled wheat and then started looking for a way to make this more palatable while still healthy. This is the version in the Wikipedia and in this Dec. 1928 article from Time magazine. But a few weeks later, in Jan. 1929, they printed a letter from his son, Scott H. Perky, attempting to correct the record. The younger Perky claims that his father was not a “dyspeptic lawyer” and that a French doctor who had attended his mother was responsible for recommending boiled wheat. Of course Time stuck with “dyspeptic lawyer,” because it's just too good to let go. He also corrects the claim that biscuits were sold from baskets in Lincoln and Denver, though it is evidently true that samples were given out from covered wagons door-to-door, since one of those wagons is pictured in Out of the Cracker Barrel; The Nabisco Story, from Animal Crackers to Zuzus (p. 221). Scott Perky, who was an inventor in his own right (see below), also wrote a biography of Henry Perky, but it was apparently never published. The maintainer of the I Love Shredded Wheat site has an active request for any information on it. She lists a brand new biography, whose author had access to the manuscript.

Things get even muddier when Perky meets up with the Kelloggs, J. H. and his brother Will Keith Kellogg, who had joined him to run the Sanitarium. W. K.'s authorized biography is The Original has This Signature—W. K. Kellogg. Gerald Carson's Cornflake Crusade provides more alternatives. (I believe a pair of Carson's articles titled, “Early Days in the Breakfast Food Industry” that ran in Advertising and Selling for Sept. & Oct. 1945 were a major source for this time period in Cerealizing America.) I can only summarize without resolving the contradictions.

The process of making shredded wheat is fairly straightforward. Wheat kernels are cooked (boiled / steamed), allowed to sit for a while, and then pressed through a pair of small rollers to create strings of the cooked grain, which are then placed side-by-side to form sheets, which are folded into biscuits, which are then baked.

- Perky and Ford may have already been designing a machine to press whole, uncooked grain before hitting on the idea of boiling it.

- A lady from Denver may have shown shredded wheat to J. H. while at the San.

- Shredded wheat may have given Kellogg the idea to make flaked food.

- The boiling idea may have been borrowed in one direction or the other.

- It may have been a surprise that the shreds came out more or less continuously and had to be cut.

- The idea of cooking after the shreds were formed may have come from Kellogg's flakes.

- W. K. may have offered Perky $100,000 for shredded wheat but stopped there when he held out for more.

In any case, by 1896, the Kelloggs were producing whole grain flakes known as Granose. Once corn was used exclusively as the grain, these became corn flakes.

C. W. Post visited the Battle Creek Sanitarium for his health. He worked with J. H. on some cereal products and failed to gain interest in his proposed improvements or tried to help selling and was rebuffed or just saw more opportunity on his own. Whichever way, in 1895 he began producing a grain drink similar to Somo called Postum and in 1897 a cereal similar to Granula / Granola, known as Grape-Nuts, so called because grape sugar was formed by the breakdown of the malted barley used in making it. (And not quite as the Wikipedia suggests because grape sugar was a direct ingredient.) In 1904 he introduced a flake cereal, similar to Granose, called Elijah's Manna, which was renamed to Post Toasties in 1908.

By the turn of the 20th century there were a variety of ready-to-eat cereal brands, most of which do not survive today. And there began to be reputable scientific interest in evaluating their nutritional value. Two lists from then specifically aimed to the economical aspects of the nutrients are here and here. Likewise, here are the result of microscopic analysis to determine whether processed grains really were superior in their digestibility.

Some particularly extravagant claims were made by Post for Grape-Nuts. These led Collier's magazine to refuse to accept their advertising, which in turn led Post to undertake a campaign against Collier. Collier then sued for libel and in 1910 a jury awarded him $50,000. Collier published articles giving his side of the story and republished them in book form, documenting in particular the evidence given at the trial as to whether or not Grape-Nuts prevented, or was safe for those with, appendicitis. The case was overturned on appeal and remanded to the lower court for a new trial, which never took place. IANAL and I don't feel like paying Loislaw to read the decision, but I believe the issue was the finer points of an individual suing for damage resulting from action taken against a corporation.

A much more significant precedent setting case was Kellogg v. National Biscuit, decided by the Supreme Court on 14 Nov 1938. Here is Time's report then and a brief report from Harvard Law Review. The Court decided that shredded wheat was a descriptive name that Shredded Wheat and then Nabisco had not given sufficient secondary meaning to associate with them exclusively as a trademark, and further that the pillow shape of the biscuit was inherent in the public's idea of shredded wheat and so could not be used exclusively without perpetuating a monopoly, outweighing a lower court opinion of 1918 in Shredded Wheat v. Humphrey Cornell, which had sought to avoid confusion to consumers when shredded wheat was served without any packaging. All of this was after the original shredded wheat patent had been declared invalid in 1908 because the design had been in use for more than two years prior to application (it would have expired in 1909 anyway) and others had expired in 1912, so only trademark law was limiting competition. Additional analysis from closer to the time of the opinion can be found in many law school journals in JSTOR: 1 2 3 4, and a recent summary of the lasting influence is here.

Yet another case with consequences was Shredded Wheat v. City of Elgin, where the company sought a declaratory judgment against a law that forbade distributing direct advertisements in the city. The court declined, rather uncreatively reasoning that if the law were constitutional, they would offer no help, and if it were not they did not need to. That is, they said the only way to challenge a law was to break it. This was cited in calls for uniform principles for such judgments.

Shredded Wheat were pioneers of modern marketing.

- A selection of their magazine ads can be found in Google Books, though it seems to miss a couple of the more outrageous (and borderline offensive) ones I have in my small collection:

- Shredded Wheat vs. Beef (scan), showing that the former is pound for pound 2½ times more nutritious than sirloin steak.

- The Plucky Little Jap (scan), from 1906, right after the Russo-Japanese War, linking their military prowess to a cereal diet.

- In keeping with their linking of diet and health, for a time their boxes said, “Tell me what you eat and I'll tell you what you are,” translating Brillat-Savarin's aphorism «Dis-moi ce que tu manges, je te dirai ce que tu es.», which is also the slogan of Iron Chef.

- They published cookbooks with dietary advice where all the recipes (many of which are savory and not just for breakfast) called for their product:

- The Vital Question Cook Book (online here).

- The even stranger The Vital Question and Our Navy, 1898 (I have scanned it here), which is half the same cookbook and half photo inventory of American naval vessels from right after the sinking of the Maine, when Hearst was pushing for the Spanish-American War. The proposition is that war is caused by poor diet and nutrition: just look at all these floating machines of destruction that are therefore necessary.

- The Happy Way to Health, which starts with a discussion of health and diet, then the specific benefits of shredded wheat, then “Unsolicited Letters of Gratitude and Appreciation”, and finishes up with a few recipes with color illustrations.

- The company made their factory in Niagara Falls into a tourist attraction in its own right with guided tours, picture postcards, etc.

The long time Director of Publicity for the Natural Food Company and then for Nabisco was Truman A. DeWeese, whose 1906 The Principles of Practical Publicity (2nd edition online) covered the principles of modern advertising. He was one of the first to use the word copy in the sense of text for an ad there, just one year after the earliest citation in the OED, 1905's The Art of Modern Advertising by Earnest Elmo Calkins and Ralph Holden, who founded the first modern advertising agency on Jan. 1, 1902 with $2,000. Oddly enough, this article, which actually cites both books, gives priority to DeWeese.

According to Scott's biography (via Holechek), Perky became a vegetarian about the same time as he was setting up in Denver. By some accounts, the Cereal Restaurant, whose purpose was to promote shredded wheat and where all the dishes contained it, was vegetarian; other sources say that shredded meat in shredded wheat “cups” as one of the offerings. Perky did promote his product in the Chicago Vegetarian. But the recipes in the cookbooks are not limited: they include meat on shredded wheat. Still, his obituary does mention his vegetarian principles in the headline.

Shredded Wheat is a biscuit not only because of its shape, but also because it is in fact biscoctum 'twice cooked' (so also Italian biscotto). If one binds up the shreds somewhat tighter and cooks the result a third time, one gets the shredded wheat cracker, Triscuit. The analogy is Bread : Shredded Wheat : : Toast : Triscuit. And once Shredded Wheat was mainly for breakfast and not all meals, Triscuit was for lunch, as in this ad.

Scott H. Perky's take on shredded wheat wound them into a tight spiral (U.S. Patent 1,517,453). These were known as Muffets. They started out with the height about equal the diameter, but then got flatter. The rights were eventually sold to Quaker, who still sells them in Canada. This round shape is similar to Barbara's Shredded Wheat, which is the brand I usually have (making a collection of vintage rectangular shredded wheat bowls even sillier), although constant supply chain problems mean I sometimes settle for other brands. Barbara's shreds are somewhat thicker and the biscuit somewhat denser, though Post's larger biscuits end up weighing a little more.

I believe some shredded wheat-like products were made with a regular flour dough rather than boiled wheat, meaning that they were really just vermicelli.

A traditional food product that is even closer to shredded wheat is kadaif, sometimes known as “shredded phyllo.” It is made by pouring a thin batter of flour and water onto a large hot spinning round metal plate. I suppose that means that to a topologist a skein of kadaif is a stack of pancakes. Here are some pictures of products from a baking machine company, one of which (the pour device) is for making it. Even better, here is a video of some being made:

In Turkish, strictly speaking, kadayıf can be several kinds of pastry and telkadayıf 'wire kadaif' is the shredded wheat one. Likewise Persian رشته قطائف rišta qaṭāʾif 'wire velvet'. Arabic قطائف qaṭāʾif / قطايف qaṭāyif are different kinds of sweet dessert pancakes; the name is the plural of قطيفه qaṭīfah 'velvet', from the root قطف qṭf 'to pick (flowers or fruit)': here is the page in Lane's Lexicon and the footnote chain in his 1001 Nights to which he refers. The usual word for the shredded wheat pastry is كنافة kunāfah, root كنف knf 'to surround': here again is Lane's page and for completeness his 1001 Nights footnote. In Turkish künefe is a dish made by layering the pastry with cheese.

As I mentioned before, galaktoboureko (γαλακτομπούρεκο) is one of my wife's favorite desserts. We recently found a mix for it, though we haven't tried it yet. Since phyllo would not keep well in a box, it uses kataifi (καταΐφι) pastry. We haven't tried it yet, but since there is no baking, I imagine it will be more like crème anglaise on shredded wheat than the real thing. But I still couldn't resist getting it. This is the export packaging, with no Greek on it at all; the only two languages are English and Arabic: غالاكتوبوريكو does not get any search hits (yet). The same Balkan grocers that have it seem to have packages of kadaif from Bosnia.

Since no real text has been quoted yet in this post, a little searching finds a Turkish yemek destanı 'food epic' by a Şerife Hanım from Konya from 1896 with the following stanza:

kadı(y)fın telini kırmalı gü(n)lü

üzeri kokulu anberli gü(l)lü

pılavın üstüne getir sütlüyü

yiyelim bizler de can cemal olsun.

That is the text given here and here; a slightly different version is given here:

Kadayıfın teni kırmalı telli

Üzeri kokulu emberli güllü

Pilavın üstüne getir sütlüyü

Yiyelim bizlerde can cemal olsun

I assume the issue is modernizing the language. It should also be found on page 473 of this anthology, which I do not have access to. Snippets of it or a similar poem appear here and in an even more potentially interesting collection here, but again those books aren't available nearby. A not very literal rhyming translation is given here:

If you make kadayif, shred well the pastry,

Make sure that it's fluffy, do not break the strands.

Bake in an oven, then sprinkle with syrup.

Kadayif is known now in most other lands.

I do not feel qualified to give a more faithful translation; I only get the gist of it. I also imagine that the poem was written in the Ottoman Turkish alphabet and I would not mind seeing it that way, but I cannot bring myself to go as far as transliterating it back.

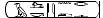

a-l-k-s-i-n-d-r-s. The surviving version of Pseudo-Callisthenes evidently comes from Egypt. To legitimize this rule, it makes Alexander the half-Egyptian son of Nectanebo. This is

a-l-k-s-i-n-d-r-s. The surviving version of Pseudo-Callisthenes evidently comes from Egypt. To legitimize this rule, it makes Alexander the half-Egyptian son of Nectanebo. This is  nḫt ḥr ḥbt mri ḥtḥr, adding 'beloved of Hathor'; other gods are presumably possible. The

nḫt ḥr ḥbt mri ḥtḥr, adding 'beloved of Hathor'; other gods are presumably possible. The